After a hiatus, I'm returning to covering the 2010/2011 reissues by Harper Collins of all of Len Deighton's major novels - running my eye in particular over the new designs and determining if there's much new for readers to enjoy.

Having so far covered all the four 'un-named spy' novels and the first four novels of the Bernard Samson triple trilogy, we're up to

Spy Line, the book which provides the anchor for the whole story arc right starting with the first novel,

Berlin Game. It sets up the denouement of the central narrative - Bernard's wife Fiona's defection to the Communist and her subsequent operations to de-stable London Central, often with much success. With that, the reader thinks, all the threads in the story are neatly brought together. That is, of course, until the story takes a whole new twist in the subsequent books and the trilogy that does bring the story to an end. So Spy Line is not an ending, more of a gear change.

In

Spy Line, for Bernard Samson life has turned upside down. His wife has defected, but his new relationship with the much younger Gloria seems to be going well ... for now. He has survived the initial internal investigations concerning his role in his wife's defection, but is still under suspicion and begins the novel on the run in Berlin, where - after debriefing an undercover agent - he discovers that his KGB nemesis - Eric Stinnes - has been smuggling drugs into East Germany.

The story moves from Berlin to London and then on to Vienna, where posing as a philatelist Bernard is asked to pick up a package from a stamp auction. As various threads of his investigations into Fiona's disappearance come together, Bernard draws his own conclusions and meets Fiona who reveals she has been a double agent all this time and has, effectively, betrayed Bernard's trust. What follows is a dramatic attempt to bring Fiona back to the west during which a number of major characters are killed and the story is fantastically set up for the final three novels as Bernard starts to ask: what really happened?

The new design

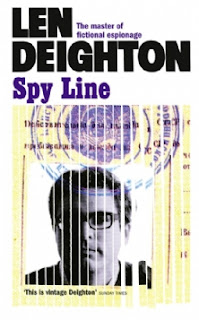

The holistic approach adopted by Arnold Schwartzman continues, with the cover image of Bernard Samson's photo on his fake Russian passport - which has been run through the shredder - illuminates the precarious balance Samson finds himself in, in which one false move could find him snatched by the Russians before he can get Fiona back.

What Schwartzman wants to symbolise here is how Samson's character, his life, is in tatters, it is ripped apart by forces beyond his control and yet he survives. However, this is perhaps the least challenging of the front covers in terms of its visual appeal.

The new introduction

Deighton writes about his approach to structuring all nine books of the three trilogies together. Although - as he points out in the introduction to each original edition - each book can be read as a stand-alone novel, clearly as an author Deighton needed to find ways to thread multiple narratives and character across nine novels (ten if you include

Winter), and Spy Hook had a pivotal role.

"In planning this Samson series I knew that Hook would record a change of mood....There was a need to reach a climax, or at least a milestone, in the overall story; a place that would prepare me, and you, for the change in style and method that Spy Sinker, the final book of the second trilogy, would use. [Deighton used a third person narrative to provide a whole new perspective on events]

My wife, and both my sons, have always maintained that my musical taste tends to favour the minor keys. Eventually I yielded to their judgement. I like the minor keys and a whole opera in a minor key is not too much for me. Spy Line is a book written entirely in a minor key. Line depicts Samson at the nadir of his life and career."

That's a great description of this story's mood.

The book also provides Deighton with an opportunity to take a deeper look at Cold War Berlin and the under-belly of the city that allowed it to function as a capitalist enclave within a Communist country. Samson's long discussions with one of his father's former agents, 'Lange' Koby, for example, illustrate the harsh reality of life in Berlin for those on the front line of the Cold War.

"I must admit that I enjoyed investigating Berlin's underworld. Sited in what was virtually the No Man's Land of the Cold War, this milieu was unique in having a national and a political dimension. Perhaps this sad domain was no more violent than Paris, New York or London, but here in Berlin one saw that authority could be more ruthless than the criminals and more indifferent to suffering. Perhaps that was not unique to Berlin; perhaps it was more a measure of my innocence."

Spy Line remains a great book which adds new layers to the characters which the reader is familiar with but also quickens the pace to lead up to the dramatic finish where one thinks the outcome is clear cut. But as the subsequent three novels prove, this is far from the case.