"Wasserman (20. Jan. - 19. Feb.) Sie haben sich vielleicht zu sehr auf die Absichten and Ideen andere Leute verlassen. Völlige Umstellung wird Ihnen gut tun."

— Aquarius (Jan 20 - Feb. 19) You may be relying too heavily on other people's intentions and ideas. A complete change will do you good. —

This also highlights peculiarities of how each language treats dates (in the UK and first editions, the month comes first - which struck me as an Americanism in itself); these are the small things which the translator has to get right alongside the big stuff. Similarly, the US edition uses em-dashes for speech, while the German using quote marks.

Harry Palmer's employer is now in this German edition W.O.O.C.(V)., rather than W.O.O.C.(P). Of course, the department acronym is never fully explained except the P being provisional. So, here, V probably stands for Vorläufig, the nearest German translation.

In places, it also reads like some idiomatic expressions or humorous asides from the protagonist - of which there are many - have been excised, perhaps because the translator simply couldn't get what the author's meaning was for one or other specific turns of phrase. For example, this section in the UK first edition:

"Monday I got to Charlotte Street usual time. A little grey rusting Morris 1000 knelt at the curb, Alice at the controls, I was pretending I hadn't seen her when she called out to me. I got into the car, the motor revved, away we went. We drove in silence a little way then I said, 'I can't find the wet bag of cement to put my feet into,' She turned and cracked her make-up a little. Encouraged, I asked her where we were going.

'To bait a raven trap, I believe,' she said.

In the German, the quip about the bag of cement - alluding I think to the doom-laden view the protagonist has of his work with Dalby - is simply not there; presumably, either the translator couldn't find an elegant way to translate it, or he felt it might get in the way of the German readers' comprehension. So translators are, in a way, also editors.

German syntax is structured differently to English - the active verb is often at the end of a sentence, meaning as a reader you only really discover the meaning when the verb pops up at the end; with German also employing many fascinatingly complex compound nouns and longer sentences on average than English, as a reader you read with a slightly different rhythm in your head, as meaning is unravelled rather than simply presented.

Anyway, it's a cracking little edition and I'm finding it a fun exercise to read bits of a very familiar story in a different context. With German being one of the languages of Cold War espionage, it also seems apt for reading a spy novel.

I have, in my collection, editions of various Deighton novels in different languages, the most obscure being Norwegian and Romanian. That is another whole kettle of fish and I imagine it will be a long, long time until I felt able to tackle that (I speak precisely zero Norwegian or Romanian).

But, it goes to show that Deighton's works clearly had commercial and cultural appeal across Europe and other parts of the world.

I would consider this book as an interesting attempt in German of then arguably the most read thriller novel, which opened up a new genre strain in thriller writing where the reader ia made to work hard to appreciate the brilliance of the author- Deighton. Hence, it stood head and shoulders above other thrillers published at that time. I remember the print medium-yes, it was supreme then, discussing the enormous interest in translation of it in other European languages. It appears the person who translated this German version, wanted it published fast as the new genre strain was gathering pace.

ReplyDeleteWe all realised then that this first novel by Deighton was the harbinger of what the readers could expect of massive contribution by Deighton on the divided Berlin-focused cold war narratives.

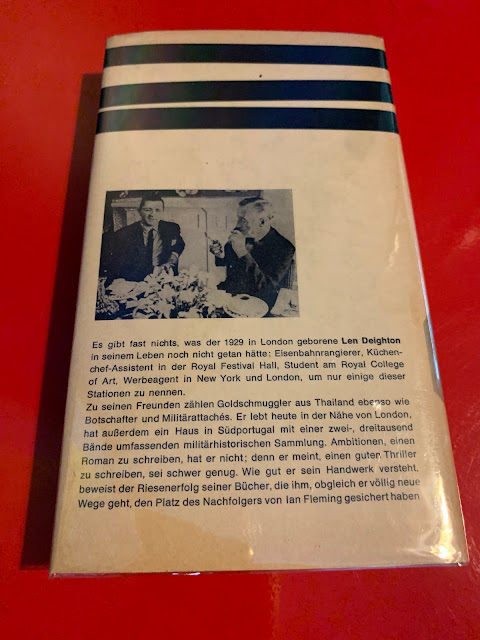

I can visualise retrospectively now, the German interest, which produced this translated version. Deighton, though catapulted into fame then, took longer for readers to appreciate his genius. But we all realised his brilliance, and his lunch meeting with Fleming cemented our appreciation of him-the reason that photograph perhaps appearing in the back cover of the book. Fleming was riding in the crest of his glory in early 1960s, after the release of the film Dr No. We thought at that time, when the news of that luch meeting appeared in the print medium, that Fleming was signalling the emergence of the above new genre strain in thriller writing under Deighton.

We were proved right when Funeral in Berlin appeared.

The rest is history..

Simon

Well said!

ReplyDelete